CEH Tools to Help You Choose Healthier Furniture

Learning Resources

The Center for Environmental Health offers webinars on healthier furniture and other products. Our webinars discuss the health and environmental concerns of chemicals used in furniture, carpet and resilient flooring, the available tools and resources to help you select healthier options, how to earn LEED and other credits by transitioning to healthier products, a review of the many ecolabels and standards in the market place and much more.

CEH partnered with Revel Architecture & Design and Kay Chesterfield Reupholsterers in this webinar to discuss healthier furniture and flooring. In this webinar, we talk about the health and environmental concerns of chemicals used in furniture, carpet and resilient flooring; the market availability of healthier, more sustainable products; how to earn LEED and other credits by transitioning to healthier products, the new GreenScreen Certified Standard for Furniture and Textiles and a case study on Reuse/Reupholstering in the San Francisco International Airport.

You may also wish to view CEH and Harvard University’s joint webinar on addressing chemicals of concern in furniture which was presented to the National Association of Educational Procurement. In this webinar, we make the human and environmental health case for selecting healthier furniture, review existing ecolabels, offer procurement tips, and Harvard University provides a case study with general guidelines for how to easily procure flame retardant free furniture. While the audience for this webinar was higher education, the principles in the webinar are pertinent for purchasers from other sectors.

To see more webinar options, visit our Resources page and filter by “webinar”.

Why to avoid the Hazardous Handful in furniture and other products

Flame retardant chemicals have been linked to cancer and other serious diseases, yet government studies have shown that these chemicals do not provide added fire safety benefits in furniture and can also increase the toxicity of the fire.

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) include numerous chemical gasses such as benzene, styrene, toluene and formaldehyde that are emitted from furniture and other products. Formaldehyde is an example of a harmful VOC that is known to cause cancer yet is still often used in adhesives found in wood furniture.

Fluorinated chemicals (PFAS), used in stain and/or water-resistant treatments in furniture are linked to serious health problems such as cancer, thyroid disruption, decreased fertility and more. PFAS chemicals can build up in our bodies and in the environment, where they can remain toxic for thousands of years without breaking down. Research also demonstrates that they don’t always provide the advertised benefits of stain repellency.

Antimicrobials in furniture have not been shown to reduce the spread of infection, can pose hazards to human health (e.g. endocrine, immune, and reproductive problems) and the environment, and may contribute to antimicrobial resistance.

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC or vinyl) is used in plastic parts of furniture and in some fabrics. PVC is a harmful material throughout its lifecycle – from its production process through end of life. PVC is produced using PFAS, asbestos and/or mercury and emissions of potent carcinogens occur during the production process and during combustion.

Flame Retardants

Flame retardants are chemicals intended to slow the start or growth of fire. Manufacturers add them to products such as foam, textiles, plastics and other products to meet flammability standards. Some of these chemicals pose human health risks and can also harm the environment.

Health and Environmental Effects

Flame retardant chemicals migrate out of furniture over the lifetime of the products and enter the air, dust, the environment, and our bodies. Flame retardants have been found in 99% of all Americans tested30 and 100% of young children tested.31 Workers involved in the manufacturing of flame retardants, the production of furniture foam and firefighting are at risk of high level exposure.32 As a class of chemicals, flame retardants break down very slowly in the environment, and build up in people and animals, often magnifying at the top of the food chain (e.g. humans). Some of the most studied flame retardants have been linked to cancer, decreased fertility, hormone disruption, lowered IQs, obesity, hyperactivity, and other serious health issues.33

As older flame retardant chemicals have been banned, regulated or withdrawn, the chemical industry has substituted them with “new” flame retardant chemicals that have been inadequately tested for human and environmental health safety. After many years of study and prolonged human exposure, these chemical substitutions are often found to be just as harmful, or even more harmful, to human and environmental health as the ones they replaced. These types of “regrettable substitutions” are far too commonly practiced by the chemical industry and place all of our health at jeopardy.

Removing flame retardants from furniture

Flame retardants were widely used in furniture from the 1970’s-2016 due to a mandatory, but ineffective, furniture flammability standard (Technical Bulletin 117). Over the years, government and research studies showed that flame retardant chemicals did not reduce the number or severity of these fires.34 After almost 40 years of human and environmental exposure, an effective group of allies including CEH and other nonprofits, scientists, firefighters and even members of the furniture industry, all advocated for a new flammability standard that would maintain fire safety and could be met without the use of toxic flame retardants. This effort was greatly aided by the Chicago Tribune’s investigative journalism. In 2014, an updated furniture flammability standard (TB 117-2013) was passed and in 2016 all products sold in the State of California (and virtually nationally) were required to meet the new TB 117-2013 standard. Many states have banned the sale of upholstered furniture products that contain flame retardant chemicals. The use of flame retardant chemicals in office furniture products produced after 2016 is estimated to be minimal.

Understanding Furniture Flammability Standards and Relevant Exceptions

CPSC federal flammability standard for upholstered furniture: 16 CFR part 1640

In June 2021, the US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) adopted and codified Califoria’s TB 117-2013 as the nation’s furniture flammability standard.35 It is important to note that while the federal flammability standard, like TB 117-2013, can be met without the use of flame retardants, the standard also does not prohibit the use of these chemicals. Purchasers should specify products free of flame retardant chemicals and request their products be labeled to confirm their absence.

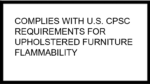

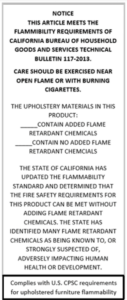

Products that meet the CPSC regulation should be labeled as noted below:

The CPSC regulation requires that any product that is manufactured, imported or reupholstered after June 25, 2022, must have a label that includes the following CPSC wording: “Complies with U.S. CPSC requirements for upholstered furniture flammability.”36

This wording can be on its own label (as seen in the first image) or can be added to the bottom of an existing California TB 117-2013 label (as seen in the second image). The CPSC labeling requirement is required but it does not override other state labeling requirements, such as the state of California’s labeling requirements for the presence or absence of flame retardant chemicals.37

This wording can be on its own label (as seen in the first image) or can be added to the bottom of an existing California TB 117-2013 label (as seen in the second image). The CPSC labeling requirement is required but it does not override other state labeling requirements, such as the state of California’s labeling requirements for the presence or absence of flame retardant chemicals.37

Exceptions to the Federal CPSC standard (16 CFR part 1640)

There are several exceptions to the federal standard and we recommend you check with your local Authority Having Jurisdiction to learn what is considered a “public occupancy” or “special occupancy” building in your state and which flammability standard may apply to your space.

“Special Occupancy” Buildings: TB 133 and ASTM E1537. Upholstered furniture that is used in specific “special occupancy” buildings (such as hospitals, other healthcare settings and prisons) is typically required to meet furniture flammability standard Technical Bulletin 133 (TB 133) or ASTM E1537. Products that meet TB 133 or ASTM E1537 are typically made with large amounts of flame retardants in the foam, fabric and/or barrier material and are more expensive (20%-50%) than TB 117-2013 furniture. Additionally, there is no research that demonstrates that compliance with the TB 133 or ASTM E 1537 standard reduces either the number or severity of fires associated with furniture.

“Special Occupancy” buildings equipped with fully automatic fire sprinklers. In almost all cases, state fire codes allow these buildings to meet TB 117-2013 instead of TB 133 or ASTM E 1537, which require high levels of flame retardant chemicals. However, rare exceptions exist; for example, some states require that furniture in prisons meet TB 133 regardless of whether they are fire sprinklered or not.

State of California “Special Occupancy” buildings (TB 133 repeal). The State of California no longer requires furniture to meet TB 133 in California’s “special occupancy” buildings. Among their reasons, the State noted that “the requirement of TB 133 is unnecessary, outdated, and no longer provides a meaningful fire safety protection to consumers or to industry.”38 Additionally they pointed to the risks for the public and the industry “associated with the exposure to added flame retardant chemicals.”39 Note: Some fire codes (especially for health care settings) require compliance with either TB 133 or ASTM E 1537. In those cases, even though TB 133 has been repealed, the ASTM requirement remains and those buildings will still require flame retarded furniture.

Words of Caution on the Need for Extra “Open Flame” Standards: There have been efforts promoted by some standards setting organizations and testing labs, often influenced by the chemical industry) to develop an additional flammability standard. The type of test they are promoting, an “open flame test”, could reintroduce the use of flame retardant chemicals and would require the use of the testing labs’ expensive testing services. There are no studies to show that these types of extra “open flame standards” would reduce the risk or severity of fires or save lives in real world situations. For organizations concerned about fire safety, the most effective strategies to reduce fire risk is through the use of automatic fire sprinkler systems, restricting smoking to outdoor areas, ensuring your smoke alarms have working batteries and occupants practice periodic fire drills. If your organization is contacted by a testing group, standards organization or other group suggesting that you consider adopting an additional “open flame” standard for your organization, please contact CEH for further information on why this is unnecessary. For more information, watch the webinar on Purchasing Fire-Safe Healthier Furniture: Great News & Concerns.

Beware of standard setting and testing organizations that suggest adoption of an additional “open flame” standard. Please contact CEH for further information on why this is unnecessary.

- Recommendations:

Specify that all furniture products meet TB 117-2013 and be labeled (as per Section 1374.3 of Title 4 of the California Code of Regulations) indicating that flame retardant chemicals were not added to the product. - For the products that must meet TB 133 or ASTM E1537 and therefore will necessitate the use of flame retardant chemicals, use CEH’s sample technical specifications when you are issuing a Request for Proposals or Invitation to Bid to avoid the most harmful flame retardant chemicals.

- Check with your local Authority Having Jurisdiction to make sure you know which flammability standard may apply to your space.

- Although the flame retardant chemical disclosure label is only required for products sold in the state of California, most large manufacturers are using it nationwide. Ask your manufacturer to provide this label to help you confirm that you have received products free of hazardous flame retardant chemicals and also to help you identify healthier furniture during office inventories. Note: The label is typically located on the bottom of a chair or under the cushion of a couch.

Volatile Organic Compounds (including formaldehyde)

The term volatile organic compounds (VOCs) includes numerous chemical gasses emitted from certain solids and liquids. When you smell the “new car smell,” it is likely that smell is from VOCs “off gassing” out of the product. One of the most well known VOCs is formaldehyde, which is used mainly in the production of adhesives for wood products, but there are many other VOCs of concern including benzene, styrene, toluene, carbon tetrachloride, and more. Concentrations of many VOCs are consistently higher indoors than outdoors by up to ten times.40 The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) stated that “the highest levels of airborne formaldehyde have been detected in indoor air, where it is released from various consumer products such as building materials and home furnishings.”41

Health and Environmental Effects:

VOCs may have both short- and long-term adverse health effects. The US EPA notes that health effects from formaldehyde include eye, nose, and throat irritation; headaches, loss of coordination, and nausea; and damage to liver, kidney, and the central nervous system. Exposure to formaldehyde also has been found to cause breathing problems.. Some VOCs are suspected or known to cause cancer in humans. Formaldehyde has been classified as a carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration, as well as the US National Toxicology Program.

Formaldehyde Emissions and Regulation: All furniture (manufactured in or imported into the U.S.) containing composite wood materials, including hardwood plywood, particleboard, or medium density fiberboard, used in office, classroom, or healthcare furniture products must be certified and labeled as compliant to the emissions standards specified in the US EPA’s Toxics Substances Control Act Title VI label 40CFR 770.42 The certification and labeling help to ensure that products entering our supply chain do not exceed the allowable amount of formaldehyde emissions.

Recommendations for Purchasers:

VOC Emissions: To help ensure healthy indoor air quality, all furniture should meet, at minimum, the reduced VOC emissions criteria specified in the ANSI/BIFMA standard (Credits 7.6.1 and 7.6.2). Greenguard Gold and SCS Indoor Advantage Gold are ecolabels that confirm these lower VOC emissions. These VOC criteria cap the amount of total VOCs emissions allowed and also require that no individual VOC exceeds a specified level. To further reduce exposure to formaldehyde, furniture should additionally meet ANSI/BIFMA criterion 7.6.3 or California’s Department of Public Health Standard Method v.1.2 (commonly known as Section 01350) which requires a lower level of formaldehyde emissions. Products that are certified as UL Greenguard Gold will meet the requirements for these reduced VOC emissions. Products that are certified as SCS Indoor Advantage Gold may or may not meet the recommended lower level of formaldehyde emissions. To find out if the product you are considering meets the reduced formaldehyde emissions, check with the manufacturer or you can ask to view the product’s SCS’s certificate which will indicate whether the product meets the reduced formaldehyde emissions required in 7.6.3.

Fluorinated Chemicals (PFAS)

Per-and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) also sometimes referred to as PFCs, are often added to the surface of textiles to provide stain, oil, and/or water resistance. Over 12,000 substances have been identified as PFAS by the US EPA.43 The primarily human-made carbon-fluorine bond is one of the strongest bonds in chemistry and these chemicals do not degrade in the environment.44

Health and Environmental Effects:

Fluorinated compounds and/or their breakdown products have been found to migrate out of furniture and “wear off” of these products with abrasion and use. These chemicals get into our air, dust, water, and wildlife, and can also accumulate in our bodies. PFAS are extraordinarily persistent (they don’t break down naturally) and once in our environment, they are expected to persist for hundreds or thousands of years.45 PFAS chemicals have been “found in the blood of people and animals all over the world and are present at low levels in a variety of food products and in the environment.”46

Many of these compounds are global pollutants and are carried by air and water currents around the world. People are most likely exposed to these compounds by consuming contaminated water or food or by using products that contain these compounds.47 “Workers, such as those involved in making or processing PFAS and PFAS-containing materials and firefighters, are more likely to be exposed than the general population”.48 Ingestion of contaminated dust may also be an important route of exposure, especially for children, who ingest relatively higher levels of dust due to their small body size and their frequent hand-to-mouth behaviors.

With thousands of variations in PFAS chemicals it is very difficult to understand the human health effects of the many chemical compounds. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences found that the research that has been conducted to date shows possible links between human exposures to PFAS and a variety of adverse health effects, including “altered metabolism, fertility, reduced fetal growth and increased risk of being overweight or obese, increased risk of some cancers, and reduced ability of the immune system to fight infections.”49 Effects on the immune system50 are especially concerning in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Research has identified an association between high levels of certain PFAS chemicals and more severe courses of COVID.51

Production of two of the most notorious PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS, has been phased out in the United States due to their serious health concerns. Unfortunately, PFOA production is now a major industry in China. Also, in the US and elsewhere, the chemical industry has simply replaced these known bad actors with a new generation of PFAS chemicals, which are less studied but are showing similar problematic characteristics. A large body of scientific evidence indicates that the “new generation” of replacement chemicals (often called short-chain PFAS chemicals) are also persistent, highly mobile and pose risks to human and environmental health.52

Some states are beginning to ban the use of PFAS in various products including textiles, rugs, carpeting and/or fabric treatments. California, Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Vermont have passed bills that ban the use of PFAS in one or more of the aforementioned products. Some of these bills do not go into effect until 2023 or 2024. Several other states are also pursuing laws to ban the use of PFAS in various products.

Recommendation: Avoid purchasing furniture fabric that contains fluorinated stain treatments and instead choose thicker fabrics that are easily wipeable and can be easily cleaned with non-toxic cleaners. Also avoid fluorinated after-market sprays. You can also select darker fabrics or fabrics with patterns that help to minimize the appearance of stains and recommend users clean up spills quickly. These small steps are worth the cost of the overwhelming harm being caused to our health and the environment by PFAS.

Antimicrobials

The Center for Disease Control defines antimicrobial agents as any agent that kills or suppresses the growth of microorganisms.53 Antimicrobials are marketed and widely added to many household, personal care, and consumer products, including furniture. There are a wide variety of antimicrobials, including metallic compounds (such as silver and copper), chlorinated organic antimicrobials, quaternary ammonium compounds, and others.

Health and Environmental Effects:

Humans are exposed to antimicrobials via ingestion, inhalation, and through skin absorption. Some antimicrobials are associated with endocrine, thyroid, and reproductive problems, as well as increased allergies in children.54

There is no scientific evidence to date to show that antimicrobials in furniture provide health benefits or a reduction in the spread of infection, including Covid-19 infection, through contact with furniture.55 Dr. Schettler, author of two comprehensive literature reviews on the efficacy of antimicrobials in furniture, expressed concern that employers might feel “inclined to use antimicrobials in products to demonstrate concern even if they are of unproven value, but if this has the unintended effect of reducing strict attention to cleaning and disinfection, it could actually increase risk ”. In other words, cleaning crews may provide less frequent and thorough cleaning and sanitizing practices as they may mistakenly believe the furniture is “protected” due to the presence of antimicrobials. Their use can also provide a false sense of safety to users and it can undermine the important and proven practice of frequent hand washing.

The lack of benefit from antimicrobial chemicals was also recognized by leading health care provider, Kaiser Permanente, and in December 2015 they announced that Kaiser was banning 15 antimicrobial chemicals from use in its furniture and other interior building products. Their reasons were lack of evidence that the antimicrobials “offer any enhanced protection from the spread of bacteria and germs”, concerns about their toxicity to humans and the environment, and concerns about the threat of drug-resistant bacteria.56

Recommendation:

Given the lack of a health benefit, the potential for harm to humans and the environment, and the added unnecessary cost, purchasers should specify furniture that does not contain added or built-in antimicrobials.

In general, be wary of antimicrobial, antiviral, or antibacterial health claims that lack supporting data and ask about product effectiveness and safety. Specifically avoid chlorinated antimicrobials, quaternary ammonium compounds, and nanometals.57

Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC)

Polyvinyl chloride, also known as PVC or vinyl, is a plastic made from fossil fuels that is used widely in homes and buildings. In furniture, PVC may be used for plastic parts or can be found in some upholstery fabrics (e.g. vinyl).

Health and Environmental Effects:

There are a large number of toxic concerns around PVC throughout the entire lifecycle of the plastic.58 PVC’s production requires the use of one or more of three of the world’s most problematic substances; asbestos (a known human carcinogen), mercury (a potent neurotoxin) and/or PFAS.

PVC can release dioxin, a known carcinogen, during manufacturing, through disposal by incineration, and if it catches fire during use. PVC is often treated with phthalates, lead, and flame retardants—these additives are not chemically bound to the PVC and can migrate out of the plastic and get into dust, which can be ingested and inhaled. Exposure to consumer products containing PVC, including furniture, can lead to exposure to PVC dust and associated phthalates, which can cause adverse health effects such as endocrine disruption and asthma.59

Recommendations:

Specify furniture, including fabric, which does not contain PVC. There are thousands of fabric choices, so it is easy to select a PVC-free option. Some small plastic product parts do contain a small amount of PVC (less than 1% by weight) in cases where safer alternatives are not yet available. Although products with this small amount of PVC can still technically meet the chemical restrictions, buyers can encourage manufacturers who use small amounts of PVC to seek safer alternatives.

Furniture Certification Programs and Standards

Certifications provide a rating, score, or official endorsement that a product has met a certain standard. Many certifications for furniture exist (also referred to as standards, seals and ecolabels), but they are not all equal. Multi-attribute ecolabels cover a range of sustainability issues, while single-attribute ecolabels address only one, such as indoor air quality. Certifications can be self-declared or come from an independent third-party organization. Very few certifications ensure complete content screenings of all hazards so while a product may meet a certification, be aware that depending upon the certification, this does not mean a product is “healthy.”

Of the current certifications for furniture, CEH recommends the following three certifications to ensure the products you purchase will be free of the Hazardous Handful chemicals:

Ecolabels/Standards/Seals/Certifications that Restrict the Hazardous Handful Chemicals

- Targeted Chemical Elimination Criterion (7.4.4) in the ANSI/BIFMA e-3 2019 Standard

- GreenScreen Certified for Furniture and Fabrics

- Greenhealth Approved

“Targeted Chemical Elimination” Criterion (7.4.4) in the BIFMA level®/certification60

The BIFMA Level® multi-attribute certification is third party-verified and based on the ANSI/BIFMA e3 standard 2019, which addresses material use, energy, and atmosphere, human and ecosystem health, and social responsibility at the product, facility, and organizational level.

The BIFMA Level® multi-attribute certification is third party-verified and based on the ANSI/BIFMA e3 standard 2019, which addresses material use, energy, and atmosphere, human and ecosystem health, and social responsibility at the product, facility, and organizational level.

There is currently no mandatory requirement in the BIFMA standard that prevents certified products, even at the highest level, from containing one or more of the Hazardous Handful chemicals. To help purchasers identify healthier products, CEH and Health Care Without Harm worked with BIFMA to develop the “Targeted Chemical Elimination” (7.4.4) which mirrors the chemical restrictions in our technical specifications. This new criterion was added to the 2019 BIFMA standard as an optional credit, therefore purchasers must specifically request products that meet the “Targeted Chemical Elimination” (7.4.4.) criterion to ensure their products do not contain the Hazardous Handful chemicals. Only products that meet this criterion will meet CEH’s/HCWH’s health protective specifications. BIFMA product certification without this specific criterion does not guarantee furniture products will be free of these harmful chemicals.

The BIFMA Level® database of products can be searched for products meeting this specific criterion. To find the healthier products in the database:

- Choose Sustainability Criteria (on left side of page)

- Select ‘Targeted Chemical Elimination’

- Search further by brand, product category. etc. if needed

As of March 2023 there were over 1,200 products registered to this criterion and many others are able to meet the criterion and will likely be added. Purchasers can help to quickly build the supply of third party verified healthier products by specifying compliance to the Targeted Chemical Elimination criterion (7.4.4).

GreenScreen Certified™ Standard for Furniture & Fabrics61

The GreenScreen certification for Furniture and Fabrics is a third party-verified certification that was established in 2021. The certification requires that all products meet the Hazardous Handful requirements and it addresses additional chemicals and materials of concern. The standard also requires the use of sustainably sourced wood, addresses waste and recyclability requirements for end of life product management and requires chemical and material product transparency.

The GreenScreen certification for Furniture and Fabrics is a third party-verified certification that was established in 2021. The certification requires that all products meet the Hazardous Handful requirements and it addresses additional chemicals and materials of concern. The standard also requires the use of sustainably sourced wood, addresses waste and recyclability requirements for end of life product management and requires chemical and material product transparency.

There are three certification levels in the standard: Bronze, Silver and Gold. The higher levels require a progressively more comprehensive Restricted Substances List (RSL) and also require that chemicals used must meet more rigorous hazard evaluations. For further information on the GreenScreen Certification for Furniture and Fabrics, please refer to this Factsheet.

For a list of certified products, please visit Green Screen Certified Products. GreenScreen is a relatively new standard and the majority of products certified as of March 2023 are textiles. Purchasers can help drive manufacturers to become certified under GreenScreen by preferring products that can meet this standard, which is the most robust of the standards we recommend.

Greenhealth Approved (Previously Healthier Hospitals Healthy Interiors Goal)62

![]() In 2022, Health Care Without Harm (HCWH) phased out their Safer Chemicals Challenge for Healthier Interiors (also known as HHI) and developed a new program called Greenhealth Approved under their sister organization, Practice GreenHealth. The Greenhealth Approved seal is applicable to any purchaser, whether from healthcare, government, education or the private sector.

In 2022, Health Care Without Harm (HCWH) phased out their Safer Chemicals Challenge for Healthier Interiors (also known as HHI) and developed a new program called Greenhealth Approved under their sister organization, Practice GreenHealth. The Greenhealth Approved seal is applicable to any purchaser, whether from healthcare, government, education or the private sector.

The Greenhealth Approved program is conducted in collaboration with BIFMA and their criteria mirror the chemical restrictions contained in CEH/HCWH’s Technical Specifications. Greenhealth Approved maintains a list of products that have received the Greenhealth Approved Seal.

Note: Greenhealth Approved also offers a certification process to assess carpet and flooring products and verifies their conformance to HCWH’s criteria for safer chemicals. See the list of current Greenhealth Approved products.

OTHER STANDARDS/CERTIFICATIONS/ECOLABELS:

The standards/certifications/ecolabels listed below do not ensure that products will comply with the health protective chemical restrictions for furniture detailed in CEH/HCWH’s technical specifications. We have included their information here to help purchasers understand the broad scope of certifications and standards.

Cradle to Cradle™ is a multi-attribute ecolabel that assesses the following areas: Material Health (including toxics), Material Reutilization, Renewable Energy and Carbon Management, Water Stewardship, and Social Fairness.

Read More...

Product certification is awarded at five levels (Basic to Platinum). Products are rated for each topic category and the final overall rating is based on the lowest level achieved in any of the 5 categories. Unfortunately, the chemical restrictions in Cradle to Cradle do not adequately address all of the Hazardous Handful chemicals.

Standard Method for the Testing and Evaluation of Volatile Organic Chemical Emissions from Indoor Sources v1.2 (commonly known as Section 01350) provides environmental specifications for VOC emissions from furniture and building products.

Read More...

The California Department of Public Health sets and oversees many health-related standards, including the Standard Method for the Testing and Evaluation of Volatile Organic Chemical Emissions from Indoor Sources Using Environmental Chambers, Version 1.2 (2017). The standard practice has become widely adopted by industry, manufacturers, and the US Green Building Council’s LEED program for conducting VOC testing in small-scale environmental chambers. This is not a certification, but a standard set of VOC criteria to which third-party certifiers or qualified independent test labs test and verify. The California DPH standard only addresses VOC emissions and does not require compliance to any of the other restrictions for the Hazardous Handful Chemicals.

Greenguard Gold is a certification program operated by UL Environment, which addresses VOC emissions from furniture that affect indoor air quality.

Read More...

Greenguard provides a third-party testing program for manufacturers and a registry of interior products and materials that have low VOC emissions. There are two levels of certification: the Basic level and the Gold level. Products meeting only the basic level of certification do not meet the health protective restrictions noted in our specifications. Only GREENGUARD Gold is equivalent to the reduced VOC and formaldehyde emission requirements in our specifications. Greenguard only addresses VOC emissions and does not require compliance to any of the other restrictions for the Hazardous Handful Chemicals.

SCS Indoor Advantage Gold is a certification program developed by Scientific Certification Systems (SCS) for the VOC emissions from furniture that affect indoor air quality.

Read More...

There are two levels of certification, the Basic and the Gold level. Products meeting only the basic level of certification do not meet the health protective VOC restrictions noted in our specifications. Products at the Gold level meet the basic air emission requirements in our technical specifications but may or may not meet the higher reduced formaldehyde levels required to meet ANSI/BIFMA 7.6.3 or the California Department of Public Health Standard Method v1.1 (Section 01350). Ask for the product certificate to determine what level of reduced emissions has been achieved by the product. For products with the lowest level of formaldehyde emissions, the certificate should show compliance with ANSI/BIFMA criteria 7.6.1, 7.6.2 and 7.6.3 noted. SCS only addresses VOC emissions and does not require compliance to any of the other restrictions for the Hazardous Handful chemicals.

Sustainably Sourced Wood:

The Forest Stewardship Council’s (FSC) mission is to promote environmentally sound, socially beneficial, and economically prosperous management of the world’s forests.

Read More...

This third-party certification program ensures forest products used in certified furniture are managed and harvested responsibly. In order for wood to maintain its FSC certification, each participant in its supply chain must be FSC Chain of Custody certified. FSC does not have a listing of compliant products, rather compliant products must be labeled with the FSC trademark logo. FSC only addresses environmentally managed wood and does not require compliance to any of the restrictions for the Hazardous Handful Chemicals.

DISCLOSURE AND TRANSPARENCY STANDARDS

Standards that Promote Transparency and Full Disclosure:

Promoting transparency and disclosure of what is in a product is a very helpful process for manufacturers to undertake and for purchasers and third parties to review. It requires that manufacturers find out what is in their product and make that information available publicly so that purchasers can identify compliant or noncompliant products. These standards do not require that a product meet the chemical restrictions regarding the “hazardous handful” chemicals.

The Health Product Declaration® (HPD)63 is an open standard that provides a consistent format for reporting on the contents of building products along with the potential associated health hazards.

Read More...

A completed HPD is created and published by companies/manufacturers about their products and should be available online in the Public Repository. The HPD allows for varying levels of information disclosure regarding the product. A fully completed HPD will include a report of hazard associations. HPDs allow for the reporting of these hazard screening results, even when the underlying chemical substances may not be fully disclosed due to intellectual property and/or other concerns. It is important to note that the HPD does not assess exposure, risk or life cycle impacts.

The HPD Open Standard is harmonized with reporting for leading sustainability certification systems for buildings, such as LEED and WELL, and for building products, such as Cradle to Cradle Certified™, Declare, GreenScreen Certified™ and BIFMA LEVEL®.

![]()

Declare is a voluntary disclosure label operated by the International Living Future Institute that is similar to a nutrition label one might find on a food product.

Read More...

Manufacturers must report at least 99% of the product’s ingredients and this information must be publicly available. Declare uses a color code system to identify chemicals of concern. Further information is provided on the product’s final assembly locations, life expectancy, end-of-life options, and overall compliance with relevant requirements of the Living Building Challenge.64

The Declare label does not require third party verification although manufacturers can choose to work with a third-party assessor to verify the manufacturers’ claims. Third party verification provides greater confidence as to the manufacturer’s claims. Products with Declare labels do not have to comply with the chemical restrictions noted in the CEH/HCWH technical specifications. Declare labels are helpful in promoting product transparency and are searchable on this free, public database.

For further information on existing certifications, refer to the Parson’s School of Design’s Healthy Materials Lab’s “Product Health Reporting” factsheet.

References

- McKenna ST, Birtles R, Dickens K, et al. (2018). Flame retardants in UK furniture increase smoke toxicity more than they reduce fire growth rate. Chemosphere, 196:429-439.

- US Environmental Protection Agency (2013). America’s Children and the Environment, Third Edition, Biomonitoring: Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs). Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-11/documents/biomonitoring-pbdes.pdf.

- Butt CM, Congleton J, Hoffman K, et al. (2014). Metabolites of Organophosphate Flame Retardants and 2-Ethylhexyl Tetrabromobenzoate in Urine from Paired Mothers and Toddlers. Environmental Science & Technology, 48(17):10432–8.

- Gravel S, Aubin S, Labrèche F (2019). Assessment of Occupational Exposure to Organic Flame Retardants: A Systematic Review. Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 63(4):386-406.

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Flame Retardants. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/flame_retardants/index.cfm.

- US Consumer Product Safety Commission (2012). Staff Cover Letter on Upholstered Furniture Validation Memoranda. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/ufmemos.pdf.

Babrauskas V, Blum A, Daley R et al. (2011). Flame Retardants in Furniture Foam: Benefits and Risks. Fire Safety Science, 10:265-278.

- US Consumer Product Safety Commission. Upholstered Furniture Business Education. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.cpsc.gov/Business–Manufacturing/Business-Education/Business-Guidance/Upholstered-Furniture.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Department Of Consumer Affairs, Bureau Of Electronic And Appliance Repair, Home Furnishings And Thermal Insulation (2018). Final Statement Of Reasons: Amendment of Flammability Standards. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://bhgs.dca.ca.gov/laws/famability_fsor.pdf.

- Ibid.

- US Environmental Protection Agency, Indoor Air Quality. What are Volatile Organic compounds (VOCs)? Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/what-are-volatile-organic-compounds-vocs#:~:text=Volatile%20organic%20compounds%20(VOCs)%20are,ten%20times%20higher)%20than%20outdoors.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Formaldehyde. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/formaldehyde.pdf.

- US Environmental Protection Agency (2018). Small Entity Compliance for Formaldehyde Standards in Composite Wood Products. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-04/documents/small_entity_compliance_for_formaldehyde_standards-importers_distributors_retailers_4.20.2018.pdf.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. PFAS Analytic Tools. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://echo.epa.gov/trends/pfas-tools.

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/pfc/index.cfm.

- State of Washington, Department of Ecology. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Retrieved January 2023 from: https://ecology.wa.gov/Waste-Toxics/Reducing-toxic-chemicals/Addressing-priority-toxic-chemicals/PFAS.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. PFAS Explained. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/pfas-explained.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Biomonitoring Program. Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFAS). Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/PFAS_FactSheet.html.

- Laitinen JA, Koponen J, Koikkalainen J, et al. (2014). Firefighters’ exposure to perfluoroalkyl acids and 2-butoxyethanol present in firefighting foams. Toxicology Letters, 231(2):227-32.

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/pfc/index.cfm.

-

Grandjean P, Andersen EW, Budtz-Jørgensen E, et al. Serum Vaccine Antibody Concentrations in Children Exposed to Perfluorinated Compounds. JAMA. 2012;307(4):391–397.

Kielsen K, Shamim Z, Ryder LP, et al. (2016). Antibody response to booster vaccination with tetanus and diphtheria in adults exposed to perfluorinated alkylates. Journal of Immunotoxicology, 13:270–3.

- Grandjean P, Timmermann CAG, Kruse M, et al. (2020) Severity of COVID-19 at elevated exposure to perfluorinated alkylates. PLoS One, 15(12):e0244815.

-

Li F, Duan J, Tian S et al. (2020). Short-chain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in aquatic systems: Occurrence, impacts and treatment. Science Direct, 380: 122506.

Lee LS (2019). Letter to the California State Water Resources Control Board regarding: Product – Chemical Profile for Carpets and Rugs Containing Perfluoroalkyl or Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://dtsc.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2020/02/Review-Lee_a.pdf.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008). Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/disinfection/glossary.html.

- Bertelsen RJ, Longnecker MP, Løvik M, et al., (2013). Triclosan exposure and allergic sensitization in Norwegian children. Allergy, 68(1):84-91.

Halden RU (2014). On the Need and Speed of Regulating Triclosan and Triclocarban in the United States.

Environmental Science & Technology, 48 (7), 3603-3611. - Schettler, T (2020). Antimicrobials in hospital furnishings: Do they help combat COVID-19?. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://noharm-uscanada.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/6513/Antimicrobials%20and%20COVID-19%20-%20August%202020.pdf

Schettler T (2016). Antimicrobials in Hospital Furnishings: Do They Help Reduce Healthcare-Associated Infection? . Retrieved January 2023 from: http://sehn.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/03/Antimicrobials-Report-2016.pdf - PR Newswire (2015). Kaiser Permanente Rejects Antimicrobials for Infection Control. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/kaiser-permanente-rejects-antimicrobials-for-infection-control-300191913.html.

- Green Science Policy Institute. Antimicrobials in the time of coronavirus. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://greensciencepolicy.org/docs/antimicrobials-in-consumer-products-building-materials.pdf.

- Schettler, T (2020). Polyvinyl chloride in health care: A rationale for choosing alternatives. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://noharm-uscanada.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/6222/Polyvinyl%20chloride%20in%20health%20care%20-%20A%20rationale%20for%20choosing%20alternatives%20-%201-31-2020.pdf

- Jaakkola JJ, Knight TL (2008). The role of exposure to phthalates from polyvinyl chloride products in the development of asthma and allergies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives, 116(7):845-53.

US Consumer Product Safety Commission (2014). Chronic Hazard Advisory Panel (CHAP) on Phthalates. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.cpsc.gov/chap. - Business and Institutional Furniture Manufacturers Association (BIFMA). Level® by BIFMA. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://www.bifma.org/page/level.

- GreenScreen Certified™ Standard for Furniture & Fabrics. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://greenscreenchemicals.org/certified/furniture-fabrics.

- Green Health Approved Furnishings. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://greenhealthapproved.org/greenhealth-approved-furnishings.

- HPD Collaborative. Health Product Declaration. Retrieved January 2023 from: http://www.hpd-collaborative.org/.

- International Living Future Institute. Declare. Retrieved January 2023 from: https://living-future.org/declare/basics/.